About The Ether Dome

The Bulfinch Building

The Bulfinch Building, named after its architect Charles Bulfinch, opened to patients in 1821 and was hailed for its modern, innovative construction. The 36,000-square-foot Greek Revival-style building was made of granite and featured windows on all sides, as well as central heating and rudimentary indoor plumbing.

“The hospital is situated at the western part of Boston on a small eminence forming part of the Charles River or bay,” noted an article in the Oct. 27, 1821, edition of the Columbian Centinel, a Boston newspaper of the day. “It is so placed that it must be forever open and accessible to the air from the south, west and east; and on the north there is considerable space between it and the nearest buildings.”

To celebrate the bicentennial of MGH’s first patient admission, we created an immersive, 3D virtual tour of the hospital’s 200-year-old original building, which is at the heart of MGH today. This behind-the-scenes view shares details from the building’s extraordinary past, including the Ether Dome and lesser-known stories, and the hospital’s exciting present. Click here to explore.

The First Operating Room of MGH

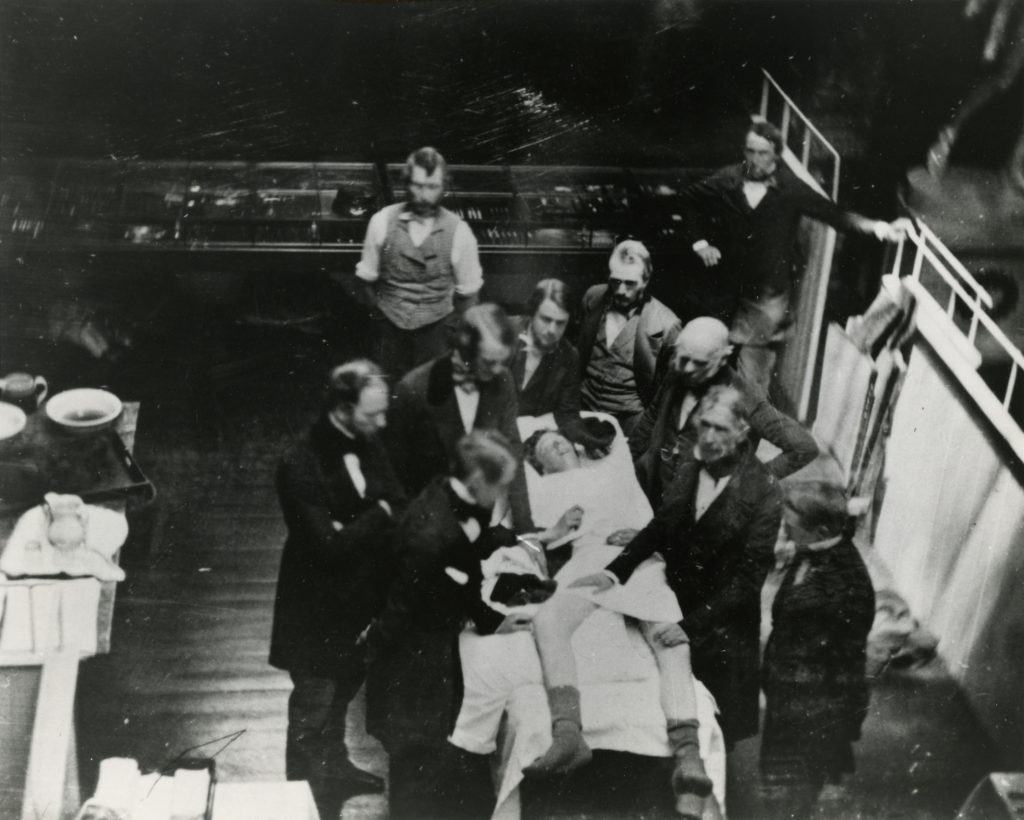

Under a dome at the top of the building, Charles Bulfinch placed the operationg theater. Operating rooms built before electricity were typically located on the top floor of a building to take advantage of available light. Before surgical anesthesia the location was supposedly helpful to make surgical patients’ cries less audible.

Because pain often induced shock, surgeons of the day prided themselves on the speed with which they could amputate an arm or a leg. Ninety seconds was considered a good time.

The operating theater, which was to become known as the Ether Dome (see below), was used for that purpose from 1821 until 1867, when a new surgical building was constructed. The Ether Dome then served at different times as a dormitory for nurses, a dining hall and a storage area.

Today the room serves as a place for meetings and lectures. The steel tiers with individual chairs date back to about 1930, when fire regulations required the replacement of the old wooden bench seating.

The Legacy of the Ether Dome

The End of Pain in Surgery

In 1844 Hartford dentist Horace Wells noticed the painkilling effects of nitrous oxide at an event where volunteers inhaled the gas and then stumbled around. Such affairs were known as “frolics.”

Wells used nitrous oxide in his dental practice for the painless extraction of teeth. In 1845 he attempted to demonstrated his discovery in Boston. The test failed, probably because the dose was inadequate. Soundly ridiculed, Wells became deeply discouraged.

William T.G. Morton, a partner in Wells’s practice, learned the technique and began experimenting on his own. Morton’s interest in using the method for surgical anesthesia was inspired by Wells but he also benefited from conversations with Charles T. Jackson, a professor of chemistry at Harvard, who advised him to use a higher grade of sulfuric ether. Jackson seemed to know that the gas could be effective in surgery, but he made no effort to apply his knowledge.

With the help of MGH surgeon Henry Jacob Bigelow, Morton persuaded MGH co-founder and surgeon John Collins Warren to allow him to try his technique on a surgical patient. The demonstration took place in the Ether Dome on October 16, 1846. The patient – a young printer named Gilbert Abbott, who had a vascular neck tumor – announced that he had felt a scratching sensation, but no pain. Warren turned to the observers and proclaimed; “Gentlemen, this is no humbug.” Bigelow immediately published an article describing the event and news traveled to Europe and other parts of America.

The Ether Controversy

Wells, Jackson and Morton each claimed credit for the innovation, with Morton emerging as victor after petitioning U.S. Congress to be recognized as the rightful “inventor.” Jackson and Morton tangled in a bitter legal dispute and pamphleteering war that lasted 20 years. Jackson died at McLean Asylum in Belmont, Mass. In 1868 Morton read a newspaper item asserting that Jackson deserved the lion’s share of credit. He became feverish, threw himself into a pond in New York’s Central Park and died, probably from a stroke, soon thereafter.

Wells left the practice of dentistry and his family and went to New York, where he was arrested for throwing acid on sex workers. He killed himself in jail by slashing an artery after taking chloroform.

Meanwhile a small-town Georgia doctor named Crawford Long had performed operations using ether as early as 1842, but didn’t publish his results until 1849, so he received no credit for the innovation.

Following the historic operation at MGH, Gilbert Abbott was discharged on December 7, 1846. He married in 1850, fathered two children and enjoyed a successful career. He died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1855 at age 30.

In the Ether Dome

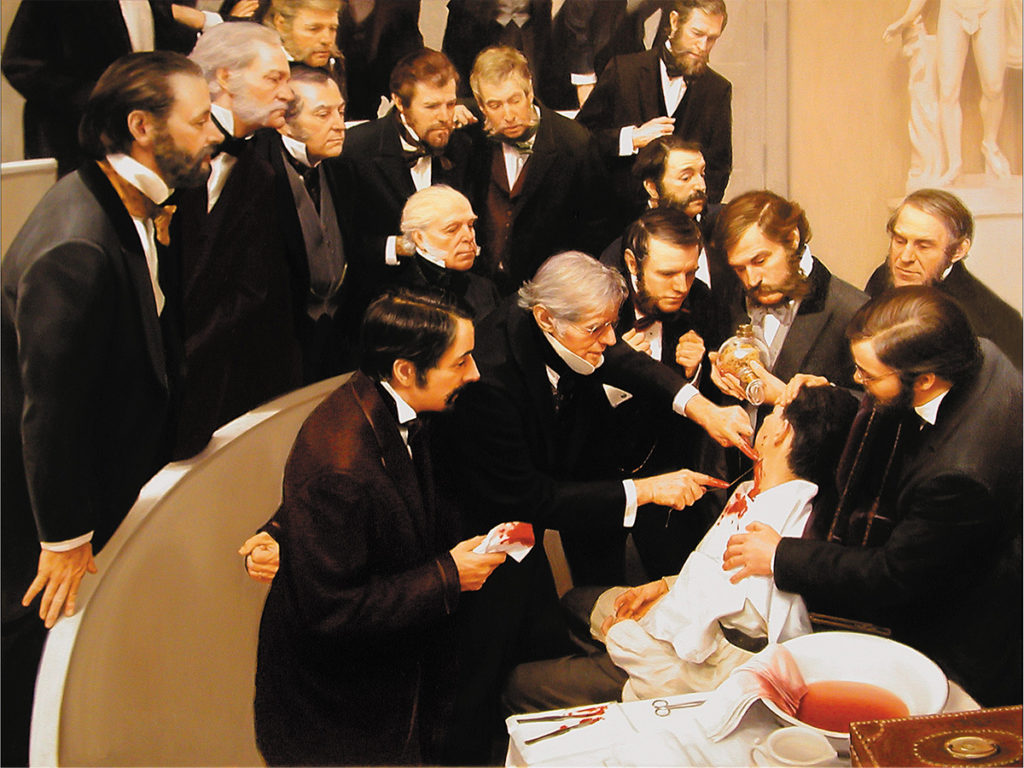

“Ether Day, 1846”

Artists Warren and Lucia Prosperi created this mural between 2000 and 2001, painting on site. To represent the historic operation as realistically as possible, the Prosperis photographed a cast of 20 men, mostly MGH physicians, who gathered in the Ether Dome in January 2000 dressed in period costumes. They also consulted vintage photographs and artifacts from the MGH Archives and Special Collections.

As the mural depicts, in the years before antiseptic and aseptic surgery, a surgeon typically operated in a frock coat, as befitted the dignity of his profession. The ivory or ebony handles of his surgical instruments signaled his status but made the instruments difficult to clean. Sterile surgery was not achieved at the MGH until the 1880s.

The Hospital’s Oldest Patient

In 1823 the merchants Jacob Van Lennep & Co., honored Boston with an unusual gift: a mummy. It arrived on April 26, 1823, and was the first complete Egyptian burial ensemble to be brought to America.

The city of Boston gave the mummy to the MGH, whose trustees accepted the gift as “an appropriate ornament of the operating room,” while also hoping to exhibit the mummy to raise funds for the hospital. The mummy was first exhibited in Boston and later traveled by ship to venues along the eastern seaboard (1823 to 1824). It then returned to the MGH, but spent much of the late 19th century at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The mummy’s outer coffin has been at the George Walter Vincent Museum in Springfield, Mass., since 1932.

In 1823 MGH co-founder John Collins Warren partially unwrapped and examined the mummy. He then published the first American treatise about mummies and mummification.

In 1960, Dows Dunham, curator emeritus at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, translated the hieroglyphics on the coffins. Dunham discovered that the mummy worked as a stone mason and was named Padihershef, meaning, “He whom the god Hershef has given.” This, and that he lived around 600 BCE in Thebes, Egypt, is the sum of what is known of his life.

Padihershef’s remains have been studied by means of x-rays and CT scans. In 2013 an anonymous donor provided funds for the mummy’s restoration. During the procedure, Padihershef was given a full-body CT scan overseen by MGH radiologist Rajiv Gupta. The results were analyzed and published by forensic pathologist Jonathan Elias. The restoration also included replacing the mummy’s glass and wooden case with a climate-controlled enclosure.

The Apollo Belvedere

Statesman, orator and short-term Harvard president Edward Everett gave MGH the Ether Dome’s plaster-cast statue of Apollo in the 1849s. The original, known as the Apollo Belvedere, was unearthed in Rome during the Renaissance. In the early 19th century, Napoleon’s army looted the Vatican and took the Apollo to the Louvre in Paris. The museum made and sold plaster casts of the statue, one of which Everett bought and shipped back to Boston.

The Skeleton

The teaching skeleton hanging in the Ether Dome can be seen in the background of daguerreotypes showing the administration of ether anesthesia in 1847. Such skeletons were a common feature in hospitals and medical schools in the 19th century.